It’s autumn in the Northern Hemisphere. The days are shortening, the skies are graying, and Halloween is on its way.

It’s time to think about death.

In German, the word for “death” is Tod, which comes from the same root as English death. But the word for “to die” is sterben, which has nothing whatever to do with English die. Sterben is, however, related to a completely different English word. To explain why, we need to get medieval.

See, throughout their histories English and German have had three words meaning “to die,” all from different origins and with different connotations.

Die and touwen

English die comes from either Old English or Old Norse,1 and seems to go back to a Germanic root also meaning “die.”

This root also produced a word in German: touwen. Or töuwen, or toun—it’s found in both Old and Middle High German, with as many spelling variations as you’d expect from a medieval word. It was apparently used and understood—turning up, for example, in the Rolandslied—but appears not to have been terribly common. It is not found in modern German. Like, at all.

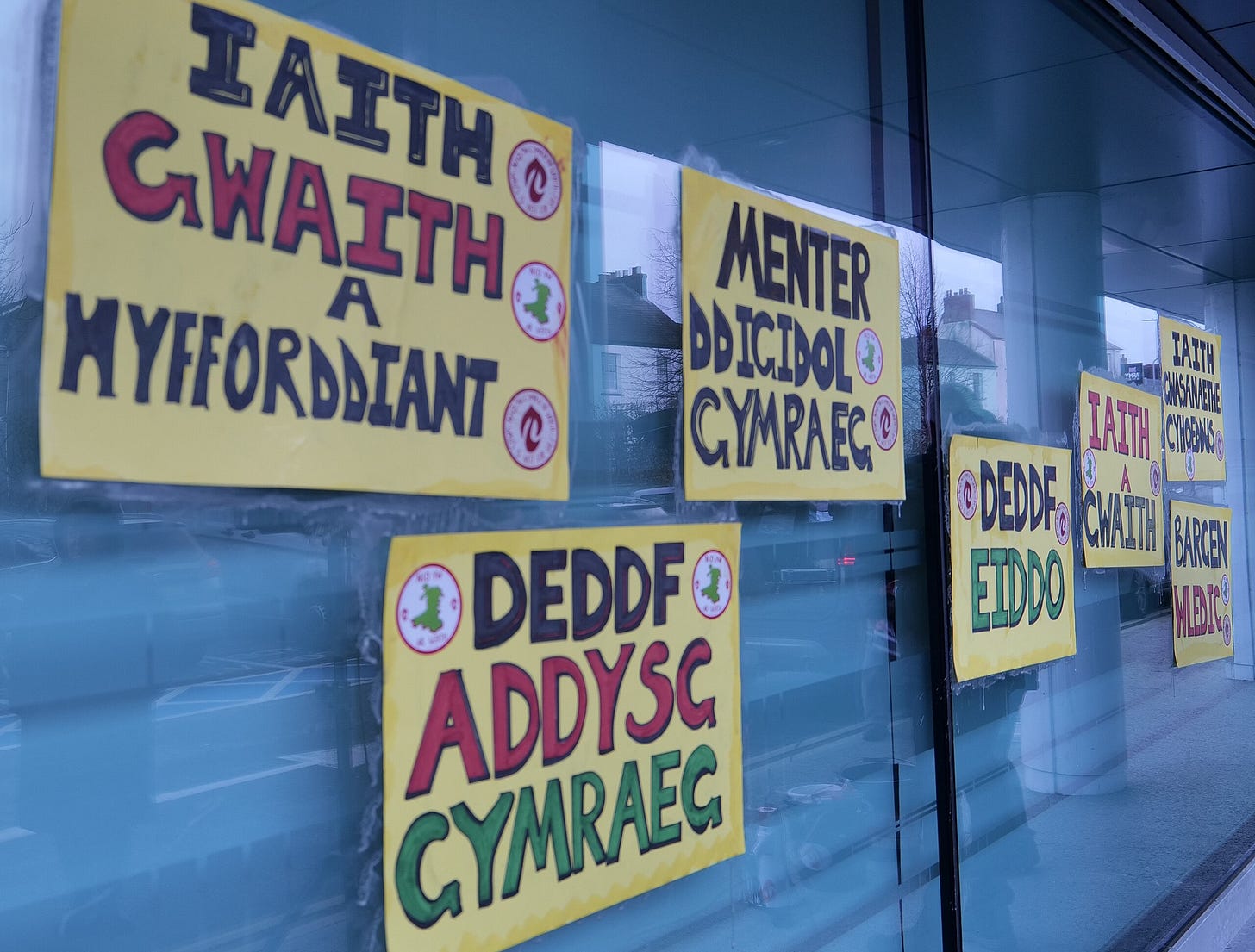

By the way, if you’ve read the Stephen King story “Crouch End,” you might now be thinking of towen, “a place of ritual sacrifice” in “the old Druid lingo.” It’s an appealing resemblance! But the language of the Druids was Brythonic, an ancestor of Welsh having almost nothing to do with the Germanic languages.2

Beyond that, towen doesn’t even seem to be a Brythonic word. It looks like King just made it up.

Swelt and swëlzen

In Old English, the most common word for “die” was sweltan. It survived into early modern English as swelt, and is also related to modern swelter.

As you might guess from that last connection, sweltan had a touch of heat to it. It comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *swel-, meaning “to burn.” You might imagine the progression of meanings was first “suffer in the heat,” then “succumb” (to anything), then “die,” but in fact it seems to have gone in the opposite direction: “die” came first, and other meanings don’t show up until Middle English.

In medieval German, the word is swëlzen (swelzen, etc.), and it doesn’t mean “to die,” only “to burn.”3 A related word, schwelen, survives in modern German. It means “to smolder” or (figuratively) “to simmer.”

Starve and sterben

Yes, sterben—which has been the ordinary word for “to die” throughout the history of the German language—is cognate with starve.

These words come, probably, from the PIE root *sterbʰ-, meaning “to stiffen.” Their earliest meanings, in German and English alike, referred to death.

Additional meanings developed in English alone: A connotation of lingering death led to the more specific meaning “to die of hunger” (in some dialects, also of cold). This led finally to the attenuated sense “to suffer hunger” (or cold) with no implication of dying, so that in today’s English one must specify starve to death.

German sterben carries none of that baggage. One can say, for example, “Sir Walter Raleigh starb 1618,” even though he was beheaded—no lingering death, that. Or, “Thomas Ashe ist heute vor 107 Jahren gestorben,” even though he died from being force-fed, and would have survived longer if he had been permitted to starve.

As we enter this numinous season, I wish you a gentler and a timelier death than theirs.

This post contains affiliate links to Bookshop.org. This means that, if you click on one of those links and make a purchase, I will receive a small part of the proceeds and Jeff Bezos won’t.

The history is a bit muddled here. The OED, for what it’s worth, calls it a “borrowing from early Scandinavian” and finds no evidence of it in Old English.

Bill Bryson observed of a Welsh-language TV show: “It was an odd experience watching people who existed in a recognizably British milieu—they drank tea and wore Marks & Spencer cardigans—but talked in Martian.”

This might conceivably include “to burn to death,” but that doesn’t seem to have been the primary meaning.