Quick links

Introduction

Video content—the proverbial “Netflix on a VPN”—is known as a good way for language learners to strengthen listening skills. It presents spoken language at natural speeds, under conditions in which you’re all but forced to make guesses and push through uncertainty, but accompanied by enough visual storytelling to provide context and (one hopes) enough entertainment value to make the whole thing palatable.

Luckily for those of us who live in text, there is a similar medium that provides exactly the same experience for written language.

Yes, I’m talking about silent films, with their rich store of intertitles—often in a demotic register and always timed to a native speaker’s reading speed. And as Halloween approaches, F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu seems an especially appropriate pick.

Nosferatu is in the public domain and can be viewed just about anywhere, in prints of varying quality and with scores of varying appropriateness. I’ll be using screenshots taken from this version on YouTube.1

It should, of course, be watched as a film.2 But this series of posts will take another approach, extracting its literary elements and presenting them in isolation. My intended audience is students of German who wish to use the text as a preview or review in conjunction with a screening of the film.

The series will be in six parts. This first part will cover the opening credits only, and is meant mainly to introduce the format and to serve as a link hub for the other parts. It will remain free.

The second through sixth parts will correspond to the five acts into which the film is divided. They will include screenshots and transcriptions of all the intertitles and of every shot containing legible diegetic text,3 with occasional, scattered notes on interesting features of the language and lettering. They will be paywalled.

Paid subscribers are welcome and encouraged to copy or excerpt these posts (in any quantity and format) for educational purposes. If you’re an educator who can’t afford a paid subscription, DM me for a comp.

Because Nosferatu dates from 1922, well before German’s most recent spelling reform, its spelling sometimes differs from that of the present day. I will transcribe the text as it stands, and generally won’t include notes on spelling differences except where in-universe documents intentionally use spellings that were already archaic at the time.

Opening credits

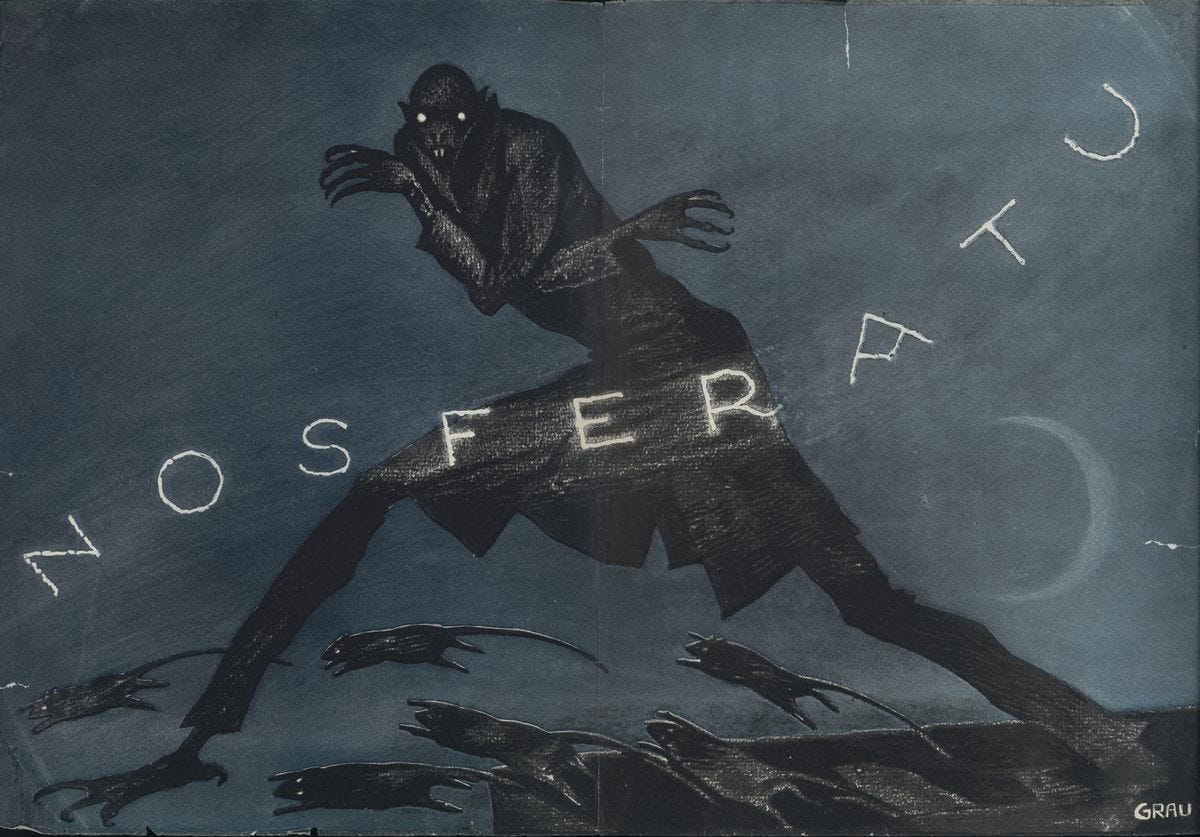

Nosferatu,

Eine Symphonie

des Grauens.

Nach dem Roman „Dracula“

von Bram Stoker.Frei

verfaßt von

Henrik Galeen.

These titles are hand-lettered, as film titles traditionally were.4 The lowercase r is similar to that in old German cursive, which creates an old-fashioned feel, but the lettering style is actually well-tuned for modern eyes to read. (Some true cursive will turn up in-universe in later scenes.)

Regie:

F. W. Murnau.

Kostüme und Bauten:

Albin Grau.

Photographie:

F. A. Wagner.

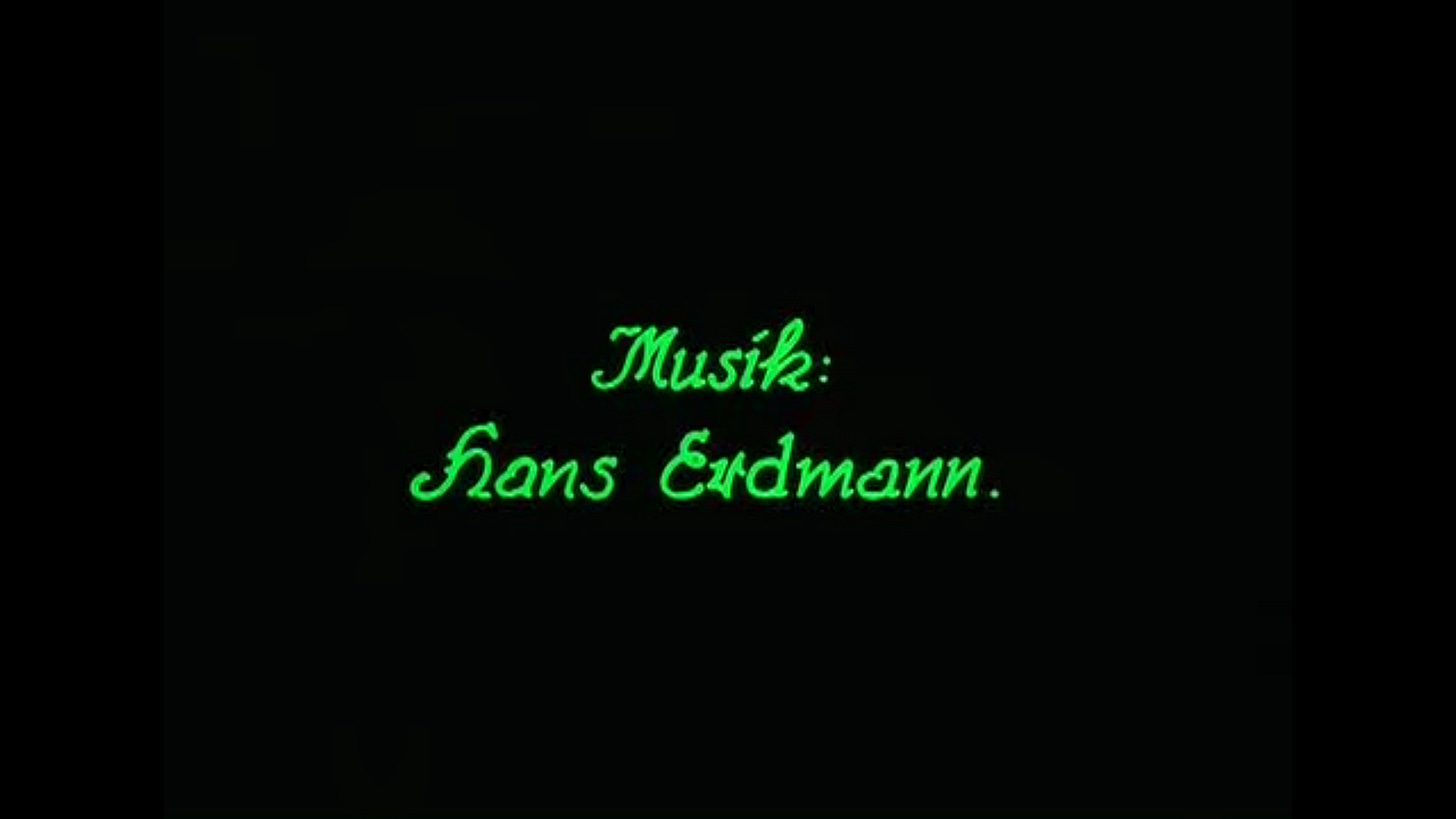

Musik:

Hans Erdmann.

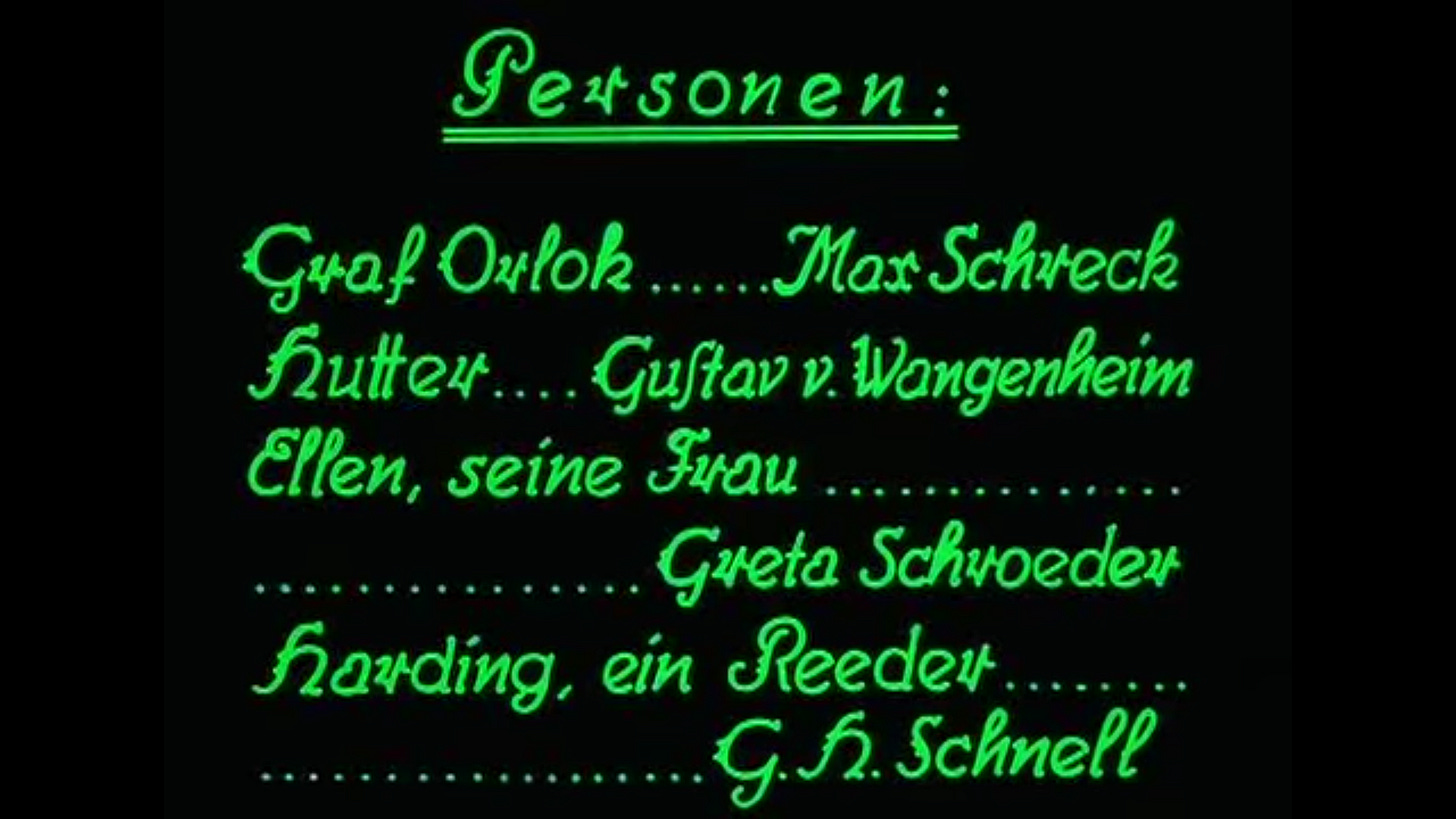

Personen:

Graf Orlok … Max Schreck

Hutter … Gustav v. Wangenheim

Ellen, seine Frau … Greta Schroeder

Harding, ein Reeder … G. H. Schnell

These titles usually avoid the long s, but it turns up here in the name Gustav. Perhaps this (and the abbreviation of von to v.) was done to help squeeze the name onto one line.

Long s will turn up in some in-universe texts later in the film.

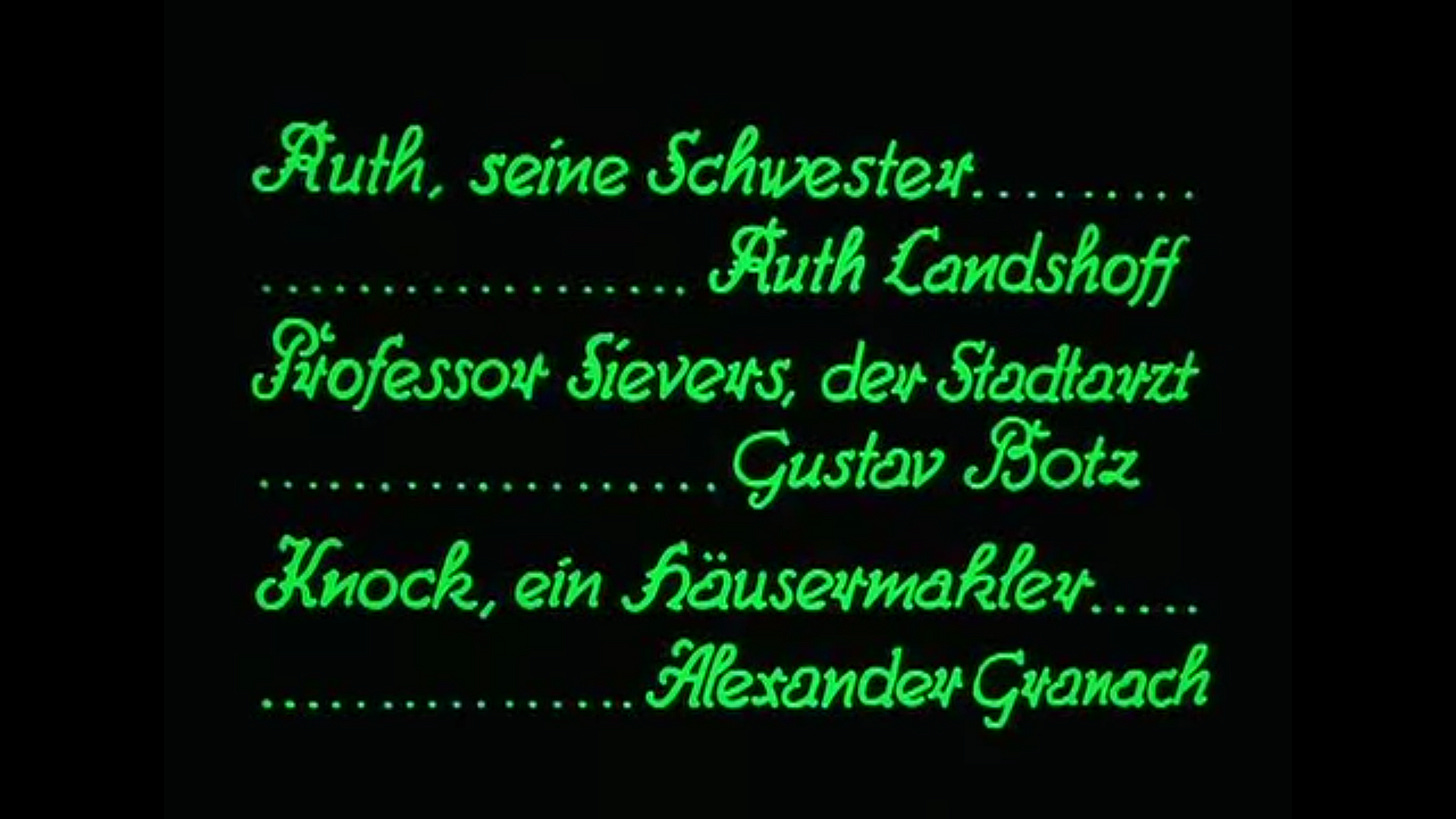

Ruth, seine Schwester … Ruth Landshoff

Professor Sievers, der Stadtarzt … Gustav Botz

Knock, ein Häusermakler … Alexander Granach

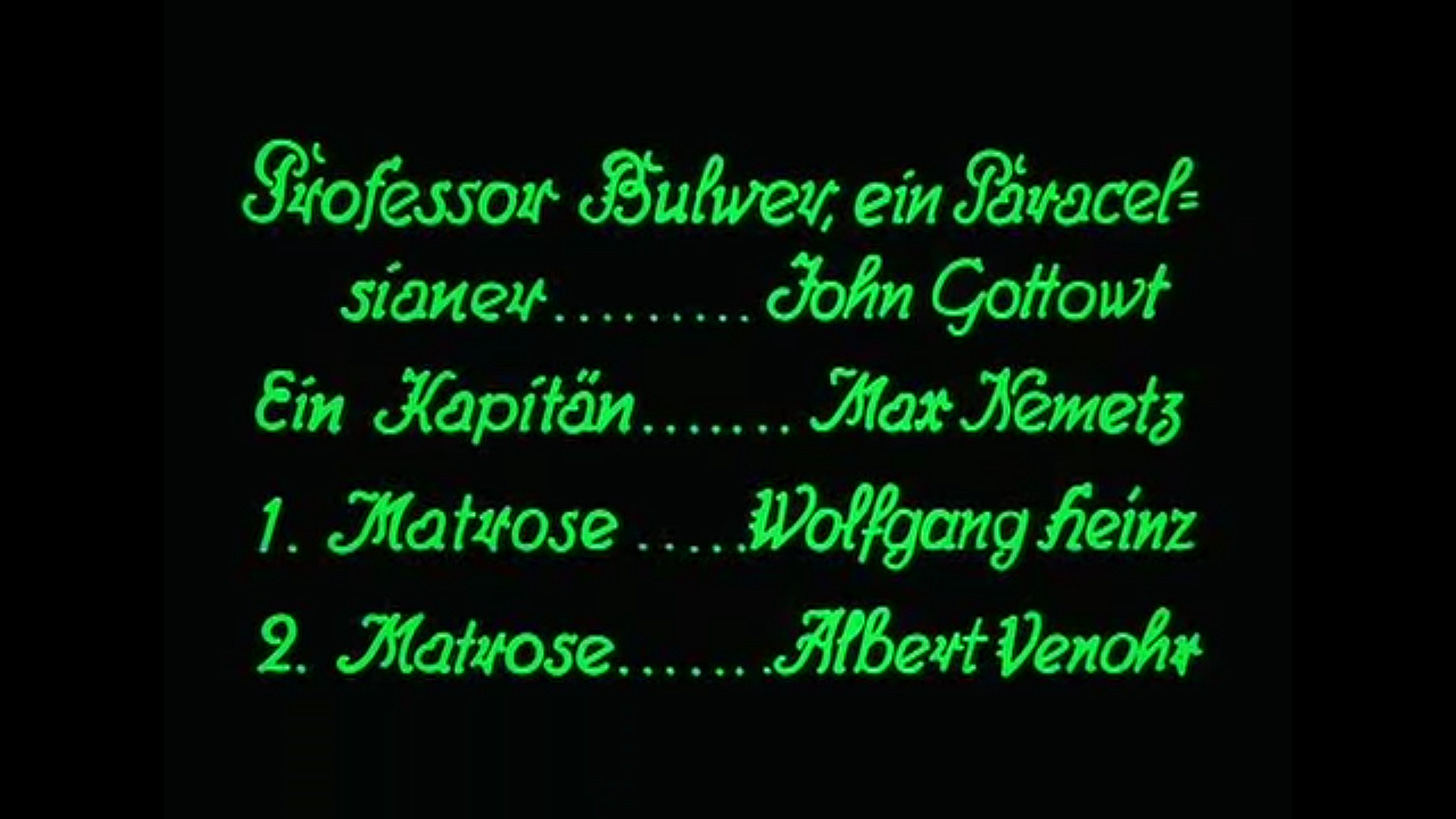

Professor Bulwer, ein Paracelsianer … John Gottowt

Ein Kapitän … Max Nemetz

1. Matrose … Wolfgang Heinz

2. Matrose … Albert Venohr

Kapitän specifically means a sea captain.

This is my cue to break off for now. Proceed to Act I?

Since this presentation includes restored tints and a score, I won’t vouch for the non/copyright status of all its elements.

By which I, being old-fashioned, mean treating it more as visual art than as literature or drama.

Or, in a few cases, diegetic text that was intended to be legible: Kurrent is a bear. I’ll sort it out for you as best I can.

Correction, 10/28/24: I originally asserted that these titles are probably re-created, based on the inclusion of a credit for Bram Stoker. This was an error: I have since read from several sources that the filmmakers always credited Stoker.

As for whether the titles are original or re-created, it seems they are original. I say this based on what I have gleaned from Brent Reid’s extensive (though frustratingly organized) series of articles on the film, which makes it clear that most of the original German titles have survived and made their way into restorations. The YouTube video I’m using as reference is probably a pirated copy of one of those restorations, though I haven’t personally done the homework to figure out which.